Authors:

Kip Holley, Principal Consultant, K Holley Consulting, kholleyconsulting@gmail.com, 711 Oakwood Ave, Columbus, OH 43205

Glennon Sweeney, Senior Research Associate, The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, Ohio State University

Jill K. Clark, Associate Professor, John Glenn College of Public Affairs, Ohio State University

Camryn Reitz, Undergraduate Research Assistant, John Glenn College of Public Affairs, Ohio State University

Date: March 1, 2024

Preferred Citation:

Holley, K., Sweeney, G., Clark, J.K., and Reitz, C. (2024). Inclusive Engagement in Area Commissions Report. John Glenn College of Public Affairs, Ohio State University: Columbus, OH. Available at: https://glenn.osu.edu/research-and-impact/inclusive-engagement-area-commissions-report

Acknowledgements:

The authors of this report are deeply grateful to our partners at the City of Columbus Department of Neighborhoods, as well as the area commissioners, who were incredibly generous with their time, wisdom, and experiences. We would also like to thank the community members and professionals who added important perspectives to our work. We continue to be inspired by the dedication of city leadership, staff, and commissioners who provide public service and create more equitable and inclusive participation environments. Finally, the authors would like to thank The Ohio State University’s Offices of Diversity and Inclusion and Research for its support of this work through the award of a Seed Fund for Racial Justice.

1.0 Introduction

What are the barriers to more equitable and inclusive engagement in Columbus neighborhoods? Researchers from The Ohio State University’s (OSU) John Glenn College of Public Affairs and The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity developed a research project in partnership with the City of Columbus Department of Neighborhoods to answer this question, focusing on the city’s area commission public engagement structure. This project had its foundation in existing research related to equitable community engagement conducted by the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, as well as extensive applied research from The Kirwan Institute assisting community members and organizations in addressing barriers to inclusive community engagement. OSU’s Office of Research awarded the partners a Racial Justice Seed Grant in December of 2020, which began a multidisciplinary research project that included meeting observations, extensive surveys and interviews, and the analysis of important documents related to area commission structure, procedure, and history. This analysis was grounded within Kip Holley’s Civic Engagement Environment Framework, which is designed to help illuminate a variety of factors that influence the inclusivity of civic engagement opportunities.

Over the next two years, the research team conducted a document analysis, numerous observations, and interviews with various people and entities connected to area commission meetings—from residents, developers, and administrators to commissioners themselves. The result was an expanded understanding of how area commissions worked, the ever-changing context they find themselves operating within, and how participants from various walks of life can have very different interactions in area commission meetings. These factors illuminate the ways in which processes, structures, relationships, and motivations conspire to place barriers to full engagement for those who are often marginalized by factors related to structural racism and other forms of systemic inequity, despite strong individual efforts to make area commission meetings more inclusive. The following report will illustrate some of these challenges while also providing recommendations for improvements based on both academic research and best practices from communities across the country.

1.1 How to Read This Report

This report details the findings of a two-year study into the City of Columbus’ area commissions and the environments they provide for community members to meaningfully engage in the business of area commissions. First, the report delivers a detailed account of the social, economic, and historical context in which area commissions were created and operate today. This is vital for understanding the challenges detailed later. Second, the report outlines aspects of the structural and procedural characteristics of area commissions, before moving on to discuss commissioners’ motivations for engaging in area commissions and perspectives of the liaisons. Finally, the report provides several initial steps that The City of Columbus can take to promote greater equity and inclusion. By this, we mean a democratic, inclusive environment, one where all community members can contribute meaningfully to creating the building blocks of their community through the full inclusion of their diverse knowledge, experience, and wisdom.

1.2 Changing Nature of Civic Engagement – Divides and Racial Reckoning

Issues related to land use, housing, and development are often marked by heightened emotions, which is understandable given how high the stakes can be for many, and how many aspects of life that land use decisions can affect. From city council meetings to homeowner associations, land use decisions often have enormous effects on one’s quality of life and personal and community identity. Moreover, regardless of individual circumstances, land use decisions are often made within environments marked by multiple jurisdictions, varying economic conditions, and ever-changing definitions of public good and private property. A passage from the publication Land in Conflict: Managing and Resolving Land Use Disputes from the Lincoln Institute of Land Use Policy states that:

Land is intimately connected to people’s livelihoods, sense of self, community, and health and well-being. Because of this, serious conflicts around land use can be expected.1

These ongoing sources of conflict in land use decisions have been more broadly exacerbated by recent changes to civic discourse. Over the latter half of the 2010s to the present, civic discourse and deliberation has undergone a set of extraordinary changes. The tenor, tone, and norms in community meetings, school board meetings, and city councils have become more contentious, with a greater acceptance of open hostility and frank discussions of a wide range of topics.2 At the same time, issues related to race and systemic inequities have come to the forefront of community deliberations at the neighborhood level in the wake of protests against racially motivated police brutality in 2020 and beyond. As a result, the role of structural racism, implicit bias, and other forms of racism and discrimination have become more likely to be points of discussion than in previous years, particularly in diverse metropolitan areas. Discussions of racial inequities have long been difficult, but the coarsening of public discourse has made resistance to the discussion of racial inequities more intense, personal, and vitriolic. Undergirding these factors is a civic environment marked by deepening distrust in public institutions and a wider variety of information sources, some of dubious quality.3 People are more likely than ever to label undesirable or uncomfortable information as ‘fake news’ or otherwise untrue, and the past decade has seen a sharp decline in already low trust with respect to public institutions and officials.4 Taken together with a context informed by historical and ongoing structural inequalities related to race and increased development pressure in a number of communities, the external factors that present challenges to equitable, inclusive, and productive engagement within area commission meetings appear formidable.

2.0 Civic Engagement Environment Framework

We undertook the investigation described in this report using the Civic Engagement Environment framework as a way to understand and conceptualize aspects of community engagement activities. Developed by Kip Holley while at The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, the civic engagement environment refers to settings (e.g., city hall meetings, community organization meetings, protests) where people interact with one another in order to deliberate, decide, and react to community decision-making (e.g., public laws, budgeting decisions) through specific contextual lenses (e.g., preferred practices, approaches to solving community challenges).

These aspects of the civic engagement environment are often communicated through a set of commonly understood cultural indicators, such as practices, identities, and assumptions that people learn throughout their lives. In civic engagement activities, these are often buttressed by laws or rules that are based on similar cultural frames of understanding. Depending on contexts and settings, people have either more or less influence over those community decisions, depending on their identities or behaviors.

The framework posits that there two general cultural frames or sets of values, objectives, and goals that provide a basis for a civic engagement environment (Table 1). First is a set of values and propositions collectively identified as ‘Strict Father’ cultural frames. This worldview, as described by author and political theorist George Lakoff, is often associated with the need for a single moral authority that must be obeyed to survive in a dangerous, self-interested world. Additionally, research into White business norms finds correlations between these views and behavioral norms related to the concentration of power and ‘winner-takes-all’ thinking.5 As a result, ‘Strict Father’ views tend to favor community engagement practices that encourage ‘winner-takes-all’ competition, strict and exclusive rules for engagement, the protection of personal property and individual economic security, and punitive measures in response to critical feedback or opposing views. ’Strict Father’ viewpoints and norms also tend to favor community engagement participants who identify as representatives of personal property or economic development issues, rather than those representing the community collectively or those who are most marginalized within the community.

Strict father

- Citizen identity: Owner; Consumer

- Laws, regulations, policies: Restrictive

- Practices: Competitive

Nurturing parent

- Citizen identity: Neighbor; Advocate

- Laws, regulations, policies: Expansive

- Practices: Self-actualizing; Collaborative

Alternatively, ‘Nurturing Parent’ describes a worldview that prizes communication and collaboration in order to make a nominally neutral world better for all. This framework expands on this definition with important contributions from feminist, racial equity, and post-colonialist scholarship to situate the definition of ideas such as ‘communication and collaboration’ and ‘better world for all’ into a broader cultural context. This translates into a worldview that favors collaborative and cooperative forms of communication and a wide range of uses for community engagement beyond decision-making, from co-learning to community-making, and a wide range of expressions of belongingness. This worldview also specifically encourages practices that address issues of social inequities and tends to approach community problems and challenges from the perspective of increased community support and correction, rather than individual punishment and ostracism.

The presence of either ‘Strict Father’ or ‘Nurturing Parent’ worldviews at the center of a given civic engagement environment is highly dependent on the worldviews of those in positions to construct and control the agenda of individual interactions within a civic engagement environment. Consequently, those who are in positions of control over creating the agenda are also in a position to ‘navigate it more successfully,’ while those who do not have access to those privileges struggle to engage meaningfully in engagement activities. The authors used this framework to help illuminate the connection between the ways in which area commission meetings struggle with providing equitable and inclusive engagement and acknowledging wider structural inequities related to race and other socioeconomic factors.

We most prominently used the framework to develop a multimodal observational tool to evaluate select area commission meetings. This tool evaluates meeting process, procedures, and individual and group behaviors with a racial equity lens informed by peer-reviewed research, as well as practical expertise in both racial equity and community engagement procedures.

3.0 Area Commissions in Context

Area commissions serve their constituent neighborhoods within the city by a) helping to create plans and policies to guide development, b) bringing neighborhood needs to the attention of city officials, c) making recommendations about neighborhood solutions, and d) promoting effective communication between the city and individual neighborhoods.6

While area commissions were designed to bring about greater engagement and transparency between residents and the city, several factors relating to social inequities, changes to civic engagement norms, and the area commissions themselves have presented barriers to the area commissions’ ability to fulfill this role to their greatest potential, particularly for those already marginalized in our communities.

While unique in some ways for a Midwestern city, Columbus developed in many of the same ways as other major American cities. An overwhelmingly White region at the turn of the twentieth century, Columbus began to change demographically when the Great Migration came to the city in 1917. Around the same time, Columbus followed a national trend of building exclusive, planned suburban developments and began using racially restrictive covenants in home deeds and declarations. As in other cities across the country, many of these restrictions were adopted into the cities’ early zoning codes.78 These restrictions include use (i.e., single-family, multi-family, commercial, etc.) and setback restrictions, as well as restrictions aimed at increasing the cost to construct, purchase, and maintain properties. They were designed to intentionally create neighborhoods segregated by both class and race.91011

New Deal policies passed during the war were integral to ensuring that post-war development would continue the trend of racial and economic segregation began around the turn of the century. One key tool used by the Federal Government came through the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) Act of 1933 and the beginning of a federal policy more commonly known as redlining, which was designed to identify investment ‘risk’ in neighborhoods. Neighborhoods of low risk were labeled A and B and identified by the colors of green and blue, respectively, while ‘risky’ neighborhoods were labeled C and D and identified with the colors yellow and red, respectively. The grade of each neighborhood was directly correlated with how ‘White’ it was perceived to be. A and B neighborhoods were all White, C neighborhoods typically were home to immigrant communities or communities with very small minoritized populations, and D neighborhoods were where minoritized communities lived. In Central Ohio, D neighborhoods were overwhelmingly where African Americans lived. Green neighborhoods were then determined to be eligible for federal mortgage insurance covering 80% of home costs, but red neighborhoods were not eligible for mortgage insurance. Banks were highly unlikely to make home loans that were not federally insured, so redlined communities and many C-graded communities (and the people residing within) were effectively shut out of the mortgage market. Many Columbus neighborhoods were redlined or graded C by HOLC, including much of Linden, King-Lincoln, Milo-Grogan, much of the South Side, Franklinton, parts of the Hilltop, and the Short North. D and C grades by HOLC were disinvestment policies for communities, resulting in rapid decline. Some of these neighborhoods continue to struggle, like the South Side and parts of Linden, while others, like the Short North and German Village, have since gentrified.

By the 1950s, Central Ohio was more segregated than it had been at the turn of the century, even though the minority population had grown significantly. Encouraged by the Metropolitan Committee, the city began a growth agenda in the early 1950s that would leverage aggressive annexation to prevent the city from becoming surrounded by suburban municipalities, making it unable to grow. Tying suburban growth boundaries to water and sewer contracts, Columbus was able to ensure pathways of growth for decades, avoiding the fate of Cleveland and Toledo – two cities completely surrounded by suburbs. These efforts were followed by aggressive lobbying at the state level, resulting in a law that decoupled school district transfers from municipal annexations, allowing the city to capture White flight at the expense of its urban school district.1213 The resulting ‘common areas’ – neighborhoods that are in the city of Columbus but attend suburban schools – became areas of intense residential development pressure in the 1960s-1990s. They are overwhelmingly located in the periphery of the city, straddling the urban/suburban divide. They include parts of the Canal Winchester, Dublin, Hamilton, Hilliard, Gahanna-Jefferson, Groveport Madison, New Albany-Plain Local, South-Western, Westerville, and Worthington school districts. Today, many of these areas are driving both diversity and poverty rates in these suburban school districts. Common areas are also overwhelmingly underrepresented by Columbus area commissions.

The following decade saw these lines of segregation solidified by the construction of the region’s highway system. Interstates 70 and 71 cut deep lines, dividing the city’s east and south sides, where minority populations had already been confined. The highways created concrete barriers between Black and White neighborhoods like Linden and Clintonville and Upper Arlington and the Hilltop, making contact between individuals living on either side unlikely. The highways were constructed in part to facilitate transportation, but the paths that they took, destroying formerly D- and C-grade, predominantly Black communities and facilitating suburban access throughout the region, gave residents the false impression that this segregation was not only permanent, but it had always existed. Central Ohio was not unique in this, as it was following a national playbook.14

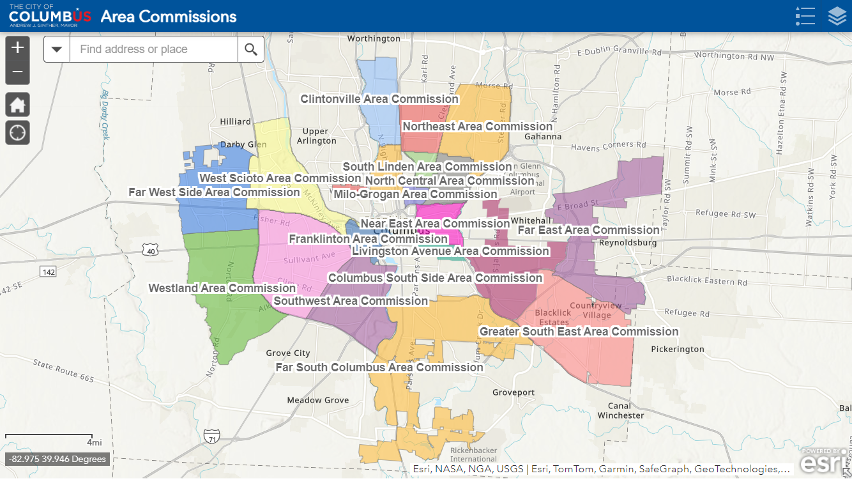

The era of highway construction was also a time when the theories guiding the field of city planning were shifting. In line with the social movements of the 1960s, planning was moving away from the rational-comprehensive model, where the planner is seen as a technical expert, and towards a new advocacy model of planning, first presented by Paul Davidoff in 1965. This advocacy model was adopted in Central Ohio and is the theoretical underpinnings for the area commissions and other participatory systems connected to development that exist today. This is evidenced by some of the earliest area commissions in Columbus, particularly the Franklinton Area Commission (1973) and the Near East Side area commission (1979). (See Figure 1 for a map of Columbus area commissions.) Both Franklinton and the Near East Side were redlined by HOLC in 1936, faced disinvestment policies, and were cut off from more prosperous parts of the city by the construction of Interstates 70 and 71. Both communities were home to marginalized populations, with the Near East Side being the hub of the city’s African American population at the time. The creation of area commissions in these neighborhoods was seen as a way to directly engage and empower these marginalized communities in development decisions.

However, recent research has demonstrated that these participatory systems, including area commissions, planning commissions, and boards of zoning appeals, among others, are often coopted by an unrepresentative group that leverages these participatory systems to delay, reduce, and prevent the production of housing in neighborhoods.15 Research has demonstrated that the members of this unrepresentative group are overwhelmingly older, White, male homeowners. Area commissions were designed, in part, to address this disparity in engagement by offering neighborhood-specific civic spaces where community and land use issues can be discussed by local residents.

4.0 Study Approach

We collected data across all area commissions and then via deeper dives into four case studies to answer the question, ‘What are the barriers to more equitable and inclusive engagement in Columbus neighborhoods?’ We collected the following data across all area commissions:

- City code and best practice recommendations: Our team reviewed Columbus City Code to understand the mandate of the area commissions and the city’s best practice recommendations (hereby referred to as ‘best practices’ or ‘best practices document’ to better understand the city’s expectations for Area commissions),

- City bulletins: Our team reviewed city bulletins from January of 2010 to July of 2021 to gain insight into how frequently the neighborhood commissions, the development commission, and the city disagreed in their recommendations for projects,

- A focus group involving city liaisons to the commissions to hear directly from liaisons about their interactions with and expectations of area commissions, and

- A survey of all commissioners to understand the motivations of commissioners, perspectives on primary constituents, attitudes towards racial equity, and relationships with city staff and officials, real estate developers, residents, and other commissioners.

Among the many neighborhood commissions throughout the city, we selected four for in-depth analysis. The team used maximum variation sampling to select these commissions, basing their decisions on development activity, adherence to city best practices, and demographics. Franklinton, Columbus South Side, Near East, and the Far East Area Commissions were selected for case studies. The team gathered the following data on these four area commissions:

- Newspaper articles focused on development in each area commission’s boundaries, as well as those focused on the area commissions themselves,

- 35 semi-structured interviews with commissioners, applicants, and community members who do not attend commission meetings to understand their experiences engaging with the Commission and their motivations for involvement, and

- Approximately 56 hours of observation of 28 area commission meetings using the civic environment rubric designed for this purpose. The rubric helps observers identify the cultural frame being used by different individuals as they interact with each other, developers, and the community during area commission meetings, enabling an observer to note instances of strict father and nurturing parent in meetings.

The main analytical approach for the data included deductive coding (structural coding) using the civic engagement framework presented in the section ‘Civic Engagement Environment framework’ (cultural frame, laws, regulation and policies, practices, and citizen identities) and inductive coding (emergent coding) to capture emergent themes.16 Given that the objective was not to count codes, but rather to interpret observation,

interviews, and documents, the team approached consensus by using intense group deliberation, or ‘dialogical intrasubjectivity.’17 Deliberation resulted in shared meaning and understanding of the data and how it related to our research question and the overall purpose of the study. The deliberative process took place during regular meetings and a retreat, starting in February 2021 and continuing through March of 2022. Our team utilized multiple approaches to address research quality and rigor, including the use of the theory-based public participation implementation framework for equitable and inclusive environments to guide analysis, prolonged engagement with neighborhood commissions, documentation, peer-debriefing while data collecting, iteration between data collection and analysis, triangulating between sources, and consensus-based coding with multiple coders.18

5.0 Findings

The first set of findings focuses on the structure of area commissions and practices. The second set presents area commission motivations, relationships, and perceptions of the structure and practices.

Columbus area commissions were formed for the very specific purpose of providing citizen input on development initiatives. Over time, that purpose has been expanded to include an array of neighborhood issues, such as public safety, affordable housing, and community support resources. Additionally, area commissions were formed at a time when development activity throughout the city was much less intense and the lack of affordable housing was not as prevalent. As such, commissions may have had time during meetings to address the neighborhood issues, while today, many struggle to make space for their issues on the agenda due to the intense development pressure that so many are experiencing. This leads to meetings with packed agendas that often leave little time for other issues.

Further, Columbus area commissions tend to follow the neighborhood lines drawn by decades of structural racism and systemic inequities. These factors have resulted in a collection of area commissions that are tied to a set of strict procedures and practices that tend to inhibit participation among residents who are often also marginalized in other areas of life. Additionally, these practices tend to favor competitive, partisan, and one-size-fits-all sentiments that make relationship building more difficult. Finally, the structures and practices indicative of area commission meetings tend to favor those familiar with norms related to White, middle-class business communication. These norms have an emphasis on time efficiency and an avoidance of conflict or emotion that tend to favor meeting behaviors that silence criticism or critique, which tend to favor those who are already privileged within any interaction. Finally, the study found a statistically significant correlation between communities that had not adopted the best practices recommended by the Department of Neighborhoods and the prevalence of Black and brown residents, suggesting that compliance with these best practices has been linked—no matter how unintentionally—with adherence to those narrow norms and expectations, rather than relevance to diverse community needs.

5.1 Area Commission Structure and Practices

Let’s begin by discussing the general structure of area commissions. They consist of between 7 and 17 members who are appointed by the mayor after an election within the commission area or by direct appointment. Members serve three-year terms, must maintain their residence, employment, or business in the commission area to stay qualified for their seat, and are considered to have resigned if they miss three regular meetings in a year.

This general structure for membership is common among sub-municipal governance structures. However, some aspects of the membership requirements and commission roster may cause challenges for greater inclusivity. For instance, the requirements make no provision for tying the number of members to the size of commission areas, nor do they make any reference to reflecting the community in terms of such factors as age, income, race, homeownership, or gender.19 Given the very real barriers related to race and income and the ability to run for government office, this has possibly led to commissions that may not fully represent the communities that they serve.20

Meeting procedures and practices vary from commission to commission, but because of their mission and nature, commissions tend to share some common practices, many based on Roberts Rules of Order. These include specific procedures, such as the keeping of minutes and requiring motions to be seconded and voted upon by commission members to be accepted.21 Many of these practices are articulated in the City of Columbus area commission Recommended Best Practices, which were developed as a result of requests from area commissioners for guidance. They aim to ‘support compliance with applicable laws, build skills, boost the level of dialogue in meetings and encourage succession planning.’22

According to the best practices document, area commissions are tasked with hearing proposals for zoning within their area and then either deciding to approve or disapprove based on a set of self-derived area zoning requirements. To the extent possible, commissions also allow time and space for resident comment and input in various ways, and many make time for participants to share news or information about important community events.23

From there, commissions pursue a wide range of practices and procedures within each meeting. Many of these are dependent on the various subcommittees and priorities of the commission. For instance, some commissions have highly sophisticated subcommittees related to housing or economic development and may include interactive activities, such as visioning sessions, in separate meetings. Others may have subcommittees dedicated to education or social impacts, and commission meetings may include more open-ended engagements with residents about those topics or meetings with various officials within the community.

5.1.1 Relating meeting structures and procedures to the Civic Engagement Environment framework

However, no practice is value neutral. According to the Civic Engagement Environment framework, civic engagement practices employed by facilitators or administrators can be categorized generally by whether they lead to closed, competitive interactions or open, inclusive actions that foster a person’s civic development. The former, which we generally refer to as Strict Father practices, is often marked by processes and structures for meeting management that favor strict adherence to predetermined engagement practices, an emphasis on meeting efficiency above all else, and practices that are more likely to result in zero-sum outcomes. Conversely, Nurturing Parent practices emphasize flexibility in process and a prioritization of building equitable and reciprocal long-term relationships between stakeholders (See the Civic Engagement Framework: Practices Table for more information on different practices). This shift in emphasis does not discount the need for consistent and efficient meetings, rather Nurturing Parent practices aim to build upon commonly understood practices for efficient community meetings to create room for greater cooperation, more diverse voices, and an emphasis on building understanding among stakeholders. Indeed, many public meeting management frameworks, such as the ‘Mutual Gains Approach and Asset-Based Community Development’ techniques, work to provide a consistent and effective structure that not only includes but takes advantage of collaboration and deliberation.2425

Our observations of four area commissions, interviews with various commissioners of the four, survey data from all area commissions, and a study of the area commission best practices document revealed a set of practices that were consistent across the four area commissions observed by the research team.

Competitive (Strict Father)

-

Outcomes of practices are meant to result in zero-sum outcomes (one winning idea/party)

-

Strict adherence to a predetermined engagement practice/style with little or no space for participants to innovate or voice criticism of practices

-

Underlying assumptions of goals/objectives based on truths from single point of objectivity that has not been co-created by participants

-

Practices encourage participants with differing views to engage in competitive processes for resources

-

Emphasis on efficiency in terms of engagement opportunities

-

Sublimation of emotional/ historical/spiritual forms of knowledge within practices

Self-Actualizing (Nurturing Parent)

-

Practice contains specific processes for amending/ changing process through engagement

-

Promoting participant empowerment/learning relevant to participant needs through engagement

-

Practice seeks or results in the acceptance of varieties of experiences, as well as knowledge that is derived from experiential and emotional sources

-

Practices are oriented towards recognizing and/or uplifting skills and abilities of participants

-

Practices prioritize building equitable, reciprocal relationships between participants and administrators

-

Practice provides mechanism or space for self-reflexivity related to social power dynamics

5.1.2 Strict adherence to a predetermined engagement practice/style with little or no space for participants to innovate or voice criticism of practices

In our observations, we found that very few practices allowed residents or commissioners space to discuss issues in a meaningful way. In many cases, this was largely due to the need to adhere closely to the parliamentary meeting procedures outlined in the area commission best practices document. For instance, these procedures often prioritize quick, concise, and efficient engagement with the public that often rewards those with specific knowledge and experience utilizing meeting procedures, such as ‘Roberts Rules of Order.’ While this system of engagement is adequate on its own, it rarely allows time or room for criticism, and those not familiar with those procedures may feel inhibited about speaking out.

Additionally, the lack of time and space to effectively have disagreements voiced and understood by all parties could further inflame already contentious issues. For instance, we found that in commissions experiencing heavy development pressure, contentious issues related to development priorities that were brought up within area commission meetings were either ignored or faced exasperation and opposition from commission members themselves, who felt that exploring the criticism would take time away from the rest of the agenda. One area commissioner summed up this perception thusly:

It used to be the next agenda item was guest speakers, if somebody wanted to come and talk to us about a program they had or something like that. What I found out was we were spending so much time on the guest speakers, the real things... I mean the meat of the meeting is to review and vote on things coming out of the committee, out of zoning committee and out of planning.

This sentiment was echoed by other area commissioners, particularly those in areas that have had relatively higher increases in zoning applications over the past few years. Examples such as these show how the rigid engagement structure of the area commissions puts commissioners under pressure to squash sometimes necessary conflict in order to stay on schedule. Additionally, because of the lack of time afforded to discussion of particularly contentious requests, votes on those requests sometimes became flashpoints for existing tensions, both those specific to the issues at hand and longstanding tensions.

Another example that was especially prescient during the height of the pandemic relates to how people are able to engage in area commission meetings. According to the best practices document, area commissions ‘may not hold meetings through teleconferencing, videoconferencing, e-mailing or through social and electronic media.’ However, special exceptions were made during the pandemic to make a number of public meetings available online. In our interviews, several attendees and commissioners alike expressed excitement over this development and felt that ending these online meetings would inhibit engagement from those who cannot attend the meetings in person due to childcare or work responsibilities. It should be noted that the City of Columbus is subject to state laws regarding public meetings.

5.1.3 Emphasizing efficiency in terms of engagement opportunities

The most common set of practices that we observed across several commission meetings emphasized time and resource efficiency. The way agenda items were brought up and discussed within the agenda was generally designed for quick comment and dismissal before moving onto the next agenda item. Moreover, our observations revealed that topics that tended to generate more contention among commissioners and/or participants were often cut short, with no mechanism for redressing previous comments.

This phenomena was also paralleled by some statements by area commissioners in interviews. When asked how contentious issues were approached, a significant number of commissioners reported being reluctant to spend much time on them. For example, one commissioner discussed deprioritizing public comment as a function of prioritizing zoning requests, remarking that ‘I requested we switch the order so the bulk of our energy and attention went to stuff that came out of committee. That's what we try to do, and the speaker thing became secondary.’ Another interviewee noted that there was a ‘lack of time for community voice, usually most of time taken up with zoning disputes and presentations…’

Finally, neither the best practices document governing area commission procedure nor our observations were able to identify many mechanisms that were specifically designed to ensure that new voices, or voices that are often unnoticed, were heard, leaving a few individuals to share the most. However, observations gathered during the Far East Area Commission, where both commissioner priorities and a policy of prioritizing community voices led to a more supportive environment for community input and deliberation, was a notable exception.

The emphasis on efficiency favored by many area commissioners is understandable given the overall mission of the area commissions. According to the area commission best practices document, the first duty of the area commission is to decide on matters related to zoning and make recommendations to the city in a timely manner. Depending on the number and complexity of zoning requests, commissions may not have the resources to facilitate meaningful discussions related to zoning conflicts. In those scenarios, research has found that those who have the fewest resources are often those who are the least likely to have input on final decisions.2627

This can be particularly challenging for area commissions representing areas of the city undergoing intense development. Our observations showed that increased development and change in these communities has generally led to an increase in conflicting views over issues of appropriateness, home affordability, and community direction. As results from both academic research and practitioner experiences have generally found, issues such as these require time, space, and effective facilitation, all of which tend to be lacking within the area commission structure.28 As a result, our observations found that conflicts over development issues tended to intensify after they’d been discussed within an area commission meeting, rather than dissipate, with parties on either side often less likely to cooperate or find a compromise.

5.1.4 Strict adherence to prescribed procedures in the face of community volatility

As mentioned earlier, dominant culture, or a Strict Father framework, favors frames of references and schemas that reward a set of actions that prioritize order, competition, dominance, and ownership over those related to cooperation, community, understanding, and tolerance. The practices present in most area commission meetings adhere to Strict Father frameworks, particularly related to order, efficiency, and competition. In interviews with various commissioners, many described feeling a great deal of pressure to prioritize efficiency and uniformity within their meetings. Subsequently, they saw little value in developing tools or techniques for expanding the space for deliberation and diversity within their meetings. One commissioner went so far as to name increased community engagement as a challenge to the area commission meeting process. Other commissioners pointed to the tension between efficiency and increased community engagement as a challenging factor in their duties.

This tension was echoed by area commission liaisons during our listening session. While the liaisons generally favored increased community engagement and greater community diversity at area commission meetings, there were important differences in how they believed that engagement should occur. Some liaisons favored techniques that decreased the presence of ‘emotion’ and other types of engagement that could lead to conflicts or other conversation that could potentially slow down the meetings. Others felt that some conflicts were necessary, and that emotion was an unavoidable part of conversations about community change, particularly due to more general societal challenges, such as affordable housing or community policing.

These differences are partially the result of strong misunderstandings by certain commissioners about the laws that govern open, public meetings in Ohio. For instance, while certain commissioners expressed deep concern over violating sunshine laws, it was very clear by their discussion that they simply do not fully understand the legislation and its impact on area commissions. Meanwhile, many commissioners did not mention these laws at all.

This appears to relate to a challenge regarding the ways in which area commissioners are prepared for their roles. According to the best practices document, area commissioners are required to attend one class (the new area commission training class) facilitated by the Department of Neighborhoods and two classes (zoning training classes) provided by the Department of Neighborhoods and the Department of Building and Zoning. Furthermore, the best practices document highly recommends that area commissioners attend various other training classes.29 During the focus group discussion with area commission liaisons, we learned that a portion of these optional trainings are designed to enhance the ability of area commissioners to engage community members, but that not all area commissioners attend them. In commissioner interviews, newer commissioners generally reported being more open to attending these trainings and standardizing rules, regulations, and procedures in area commission meetings, while long-term commissioners expressed a less favorable attitude to standardization and were less likely to report attending the trainings.

5.1.5 Encouraging participants with differing views to engage in competitive processes for resources

The clash between the need for order and efficiency and the varying ideas that commissioners have about their responsibilities appears to foment an environment of competition rather than cooperation within area commissions. This competition occurs between commission members as well as various attendees and petitioners, generally revolving around resources such as time, commission resources, and the creation of additional structures.

The rigid engagement structure of the area commissions also inhibits effective communication and transparency, particularly about topics related to zoning. As mentioned earlier, the parliamentary style of engagement in commissions tends to favor those with advanced knowledge or familiarity with laws and procedures related to that style of engagement. Furthermore, since the topics primarily revolve around zoning laws and customs, an added layer of knowledge is often required to effectively engage in area commission meetings. Many residents do not possess this knowledge, nor do they often have the time and resources to come by this knowledge quickly. While the city does offer training for area commissioners, many of them cover a range of topics related to the practicalities of the work of the area commission. Additionally, our interviews seemed to confirm wider research linking disparities in civic engagement knowledge and experience with income and wealth gaps related to structural inequities connected to race and class.30 31 32 33

5.1.6 Sublimation of emotional/historical/spiritual forms of knowledge within practices

The structure of area commission meetings also appears to effectively discount the value of input that takes the form of less standardized but equally important knowledge. Stories and narratives that contain important community knowledge or wisdom or express the socioemotional importance of place are often discounted. These types of knowledge have been pointed out as important to community character, cohesion, and quality of life in various research studies and practitioner resources.3435 This is particularly true for communities that have experienced disinvestment or have been negatively impacted by processes like segregation and urban renewal. Without this knowledge, new developments may be at greater risk of interfering with community networks or even pushing out community members due to economic or social changes. The current structure of area commissions runs the risk of missing important information that currently cannot be facilitated within their rigid structure. However, there is a caveat to the sublimation of these types of expression within area commission meetings. Within subcommittees and other activities that are more ‘people-centered’ or ‘social-centered’ (such as those related to social services or community activities), the structure appears to be more amenable to emotional expressions and lived experience than property centered work.

5.2 Area Commissions: Motivations, Perspectives, and Relationships

In this current time of changing demographics and civic engagement norms related to culture, social media, and other factors, area commissions find themselves unable to stay relevant to a wide swath of community members, and particularly people of color. Furthermore, depending on the community, and personal motivation for service, area commissions and commission members have differing relationships with developers, the city, and residents themselves. Longer-term commissioners tend to have greater trust for developers and city officials, whereas new commissioners tend to trust members of community organizations. Trust for fellow commissioners seems to be inversely tied to development pressure, particularly in communities where demographics are rapidly changing. These factors have led to a series of relationships and motivations among commissioners and stakeholders that ultimately inhibit more inclusive and equitable engagement. Undergirding this are relationships with city liaisons, who often find themselves under-supported in their efforts to help area commissions respond to these challenges and who hold differing opinions about the place of emotion and order within area commission meetings. Finally, the responses from interviews reveal that a significant number of area commissioners have a wary relationship with city officials, particularly over issues related to the area commission best practices document and other procedural rules and requirements.

The structure of area commissions and the context in which they operate have created a series of relationships between commission members and the wider communities in which they sit. The patterns of these relationships are based on a set of expectations, rituals, and responses that mirror larger trends in civic engagement over the past decades and compound many of the challenges to inclusive engagement caused by the area commission structure. Moreover, the area commission structure does not offer many options to highlight the role that relationship patterns play in adjudication in area commissions, nor do they offer any solutions for addressing relationship patterns that may—even inadvertently—impede equitable and inclusive engagement within area commission meetings.

Due to the changing nature of civic engagement discussed earlier in the report, area commissions therefore find themselves operating in a vastly different environment for civic engagement than was true at their conception. It is an environment in which participants are less likely to trust the motives of commissioners, city officials, developers, or one another, and in which there is little incentive to follow traditional rules governing public decorum. Furthermore, many participants are more aware—or more wary—of how structural inequities play a part in even the most seemingly race-neutral issues, such as zoning changes. Those who are interested in addressing these barriers have become more pointed in their criticisms and actions to address these concerns within area commission meetings, while those who are either opposed or uncomfortable with such efforts redouble their efforts to avoid those topics, with many people lying somewhere on spectrum between these two extremes.

Area commissions were not created to accommodate such discourse, as is the case with similar conventional participation structures. The regimented agenda and norms of the area commission meetings leave little time to talk through difficult issues or allow people to clarify or expand on complicated topics. Furthermore, the austere and difficult-to-understand parliamentary system of governance employed by the area commissions is often out of the grasp of both some participants and commissioners alike.

These challenges are exacerbated in area commissions that adjudicate a great deal of zoning applications due to overwhelming development pressure. In these commissions, there is even less time for deliberation and, conversely, more to discuss as housing, economic, and demographic changes in the neighborhood take hold. With no other obvious public outlet for discussion, area commissions have become the de facto place for people to vent frustrations, ask questions, and comment on their changing neighborhoods. Often, though, area commissions and commissioners have few tools to accommodate these discussions in a positive way.

The inability of area commissions to accommodate these aspects of current community engagement needs is the result of how the area commission structure and the processes that result from it interact with the city’s complex history regarding race, law, and real estate development, which creates a distinct set of practices, motivations, and identities that result in a suboptimal environment for engagement. The evidence collected as a part of this study suggests that a number of important factors combine to create a set of conditions according to which individuals (area commissioners, participants, developers, support staff, etc.) respond using pre-existing social scripts. In other words, the way that the area commissioners respond to the outcome of decades of systemic racism and changing and intensifying development patterns creates a situation that individuals respond to in the best way that they can. Unfortunately, these situations more often than not exacerbate the problems that these individuals face.

For instance, earlier in this report, we discussed the ways in which some commissioners felt the need to limit the time for public comment in meetings in order to ensure that they are able to decide on zoning-related matters in a timely manner. However, interviews with area commission participants from those same commissions reveal that this actually makes it more difficult for different participants to come together and make mutually satisfactory decisions. One interviewee stated that they and other residents struggle to gain ‘a clear picture on…what did the city want this area to look like?’ Other non-area commissioner interviewees echoed the sentiment, saying that they felt that the commissioners, city, and developers were going to ‘do what they wanted to do’ regardless of resident desires, largely because of the lack of time for comment.

The reactions of commissioners appear to play a part in the formation of a series of relationships between various individuals within an area commission meeting, as well as a set of motivations that various people have for engaging in area commission meetings, particularly for commissioners themselves. These two factors, along with the individual practices, illustrate the possibility of inclusion that exists within any area commission meetings. Below, we discuss some of these factors in greater depth.

5.2.1 ‘Service’ and its many meanings

Among commissioners, the motivations for volunteering for the commission was generally ascribed to the idea of public service or simply ‘service.’ However, when ideas of service were further interrogated, it became clear that it meant different things to different commissioners. Further, individual ideas about service had their basis in a wide variety of community member orientations and personal goals. Outside of the general idea of ‘being of service,’ the survey results revealed numerous other motivations that commissioners gave for volunteering for the commission.

Some commissioners identified a desire to get engaged in local politics, as the commission can be seen as a first step to gaining visibility and access to networks that may help them attain higher elected office. These commissioners also tended to express a greater amount of distrust of community residents, while tending to hold more favorable views of developers. They also tended to have been politically active before joining the commission.

Other commissioners have decided to join the commission because of recommendations or requests from friends and neighbors. These requests are usually related to a positive appraisal in dealing with a past community issue, or a shared political or development outlook between the commissioner and a group of friends or neighbors. These commissioners also tend to be distrustful of fellow commissioners, often because they were asked to join specifically to counter the decisions made by existing commissioners. They also reported a desire to ‘protect community character’ or to ensure home values, possibly alluding to why they were asked to join the commission.

Still other commissioners reported being motivated by a desire to challenge or change prevailing development patterns in the community. Many of these commissioners were younger or newer area commissioners and reported being less trusting of community residents. However, it is also worth noting that the survey did not further specify ‘community residents’ as a category, leaving open the possibility that different commissioners may trust some community residents more than others. Commissioners who are motivated by a desire to change development patterns also tend to be more liberal in their views, and there is evidence that they see themselves as ‘righting the wrongs’ of inequitable or unfair development practices or outcomes.

Finally, some commissioners reported being motivated by a desire to build collaborations or coalitions with local partners and residents. This group of commissioners is primarily identified by their high level of trust in community residents, their fellow commissioners, and developers. Additionally, these commissioners reported the most liberal views out of all commissioners.

The above factors play a large role in how and why people are drawn to serve on area commissions and participate in commission meetings, even as people may present those motivations or their presence within area commission meetings using neutral reasons such as ‘service’ or ‘because a neighbor asked.’ However, the way that they react to issues related to racial discrimination can be traced back to their motivations. For instance, our survey revealed that those whose motivations are based on being asked by neighbors or becoming involved in local politics are generally less likely to see aspects of racism as a problem for society or to express anger over the presence of racism. However, it must be noted that the term ‘racism’ within the survey is largely meant to mean racism as a societal or institutional problem, rather than explicit, interpersonal instances of racial discrimination, such as open animosity or use of derogatory terms.

5.2.2 Discomfort with race

When asked about the topic of race, some of the commissioners seemed uneasy with the question, while others gave vaguely positive or ambivalent answers about the way that the city’s historical and current relationship with systemic racism affects commission meetings. Those who gave more pointed answers discussed the way in which race is often ignored within the meeting, with one commissioner stating, ‘On our commission even, it's never said this is race, but you can feel it maybe a little bit. It's in there. I mean, you got some people who's been on there for a long time and stuff.’ However, many residents discussed their current struggles with the commission and increased development more broadly through their personal histories with their communities, often discussing the effects of systemic racism in between. One commissioner even noted that their commission tended to ignore an entire subset of their commission area that was primarily comprised of residents of color.

Further, we found that motivations were related to attitudes about racism. For example, commissioners who are motivated to join a commission for personal political advancement are more likely to believe that problems related to race are rare, and those commissioners who are recruited from current commissioner networks are less likely to be angry over racism, while commissioners who said they were motivated by more neighborhood-level issues (not individual issues) were more likely to acknowledge systemic racism. For example, commissioners motivated to join the commission because they want to collaborate with other neighbors are more likely to seek greater equity in society.

5.2.3 Commissioners’ claims for legitimacy

In addition to various relational clusters, area commissions are also marked by questions of standing, reputation, and the relative value of participants’ perspectives. The research revealed that participants are motivated to position themselves and their contributions as valuable to commissioners and other community members through statements that identify an appropriate standing based upon their identities. In the Civic Engagement Environment framework, citizen Identities are described as various means of self-identification within the public engagement environment designed to enhance one’s standing, particularly in times of conflict. Within area commission meetings, participants attempt to gain standing based on where they live, who they know, or their area of expertise. Specifically, the identity of a homeowner seems to be highly desirable ti participants and effective in confronting opposition. This is especially powerful when combined with a long tenure of ownership, which aligns with the ways in which the groundbreaking book, Neighborhood Defenders: Participatory Politics and America’s Housing Crisis, discusses how community members gain standing based on longevity and homeownership, among other attributes.36 So, for example, if a participant objects to a zoning application, they may begin with a phrase like, ‘As a resident and homeowner of this community for 15 years…’ to counter the perceived legitimacy of real estate developers or other businesses or institutions, who in turn may have based their legitimacy on their expertise or resources. Perceptions that long-time homeowners have more legitimacy than residents who rent or are new homeowners have been cited as barriers for the latter group of residents to participate due to a sense that they are not as ‘invested’ in the community.37 Finally, some participants feel that age is also an effective identity for standing, with seniority sometimes being imbued with experience or community knowledge. However, some residents felt that their advanced age was also used against them by younger participants, who they feel may paint them as ‘out of touch’ with current events.

5.2.4 Uncertainty in responding to meeting barriers

Responses to the exclusionary consequences of this engagement environment vary. During our research, it appeared that most area commissioners who we interviewed were aware that some people had trouble participating in a meaningful way during the meetings, but their reactions to this occurrence varied. Some commissioners were eager to find a remedy to these challenges in order to make the area commission meetings more accessible, while others felt that the exclusionary nature of the meetings was key to ensuring they were efficient and effective in their efforts to manage local development. However, a majority of respondents was generally unsure of the overall effects of the engagement environment within the commission and had no strong ideas about how to address engagement issues. Furthermore, some of the commissioners who we interviewed also expressed uncertainty as to what they could legally do to support greater diversity and inclusion within area commission meetings.

A popular suggestion from commissioners is to find ways to ensure that the commission itself was reflective of the community in terms of demographic makeup. Some commissioners described formal and informal efforts at reaching out to constituencies that were underrepresented on the commission. However, little information on results was given. While diverse representation is an important aspect of greater inclusivity and equity in community engagement activities, its presence does not satisfy the need for greater inclusivity in participants and participation methods from residents more broadly.

Another common response to the engagement challenges within area commissions is to default to strict adherence to commission rules related to decorum and procedure. Some commissioners described their reactions to challenging conversations as ‘getting the meeting back on track’ or ‘reminding people of the rules of the meeting.’ These techniques seemed to be designed to fulfill two separate but connected goals: first, to restore a sense of order and movement to the meeting, and second, to interrupt further disruption related to the disagreement. While this response is usually effective in achieving these two goals, it also has a chilling effect on future engagement, particularly among those who may hold a similar opinion or who may be connected to the residents in question through social networks. It might be directly tied to language in the best practices document regarding commissioner behavior. According to the best practices document, area commissioners should ‘conduct themselves in a professional and civil manner’ and area commissioners ‘shall treat other commissioners, developers, and members of the public with respect and consideration.’38 While these statements seem generally positive or in other ways benign at first glance, when positioned as a central set of interpersonal dialogue directives in an engagement environment marked by high levels of inequality, low understanding, and low decorum, they provide commissioners with little information or guidance for creating inclusive and healthy environments to remedy existing engagement challenges.

5.3 Liaison Perspectives

Beyond the best practices document, commissioners are also provided the opportunity to access neighborhood liaisons for guidance on a variety of issues. Liaisons are assigned a certain number of commissions, which they assist through regular attendance and assistance with zoning laws, meeting procedures, and insight from the Department of Neighborhoods and other city departments. Liaisons also provide capacity-building opportunities through the city.

Discussions with neighborhood liaisons reveal a variety of responses regarding community engagement, as well as differing interpretations of the duties that commissioners have in their dealings with meeting stakeholders. Generally, liaisons were split on the question of the place of emotion within the meetings, with some feeling that emotional reactions should be discouraged within area commissions while others expressed the importance of respecting authentic expressions by community members, including emotional responses. Those in favor of limiting emotions point to the importance of process and efficiency and tend to see emotional volatility as a detriment to cooperative community action. Other liaisons point to the relative positionality of area commissioners regarding traditional marginalized community members and raise the issue of ensuring that those voices are heard. Those dealing with the negative effects of development in the form of such issues as housing affordability and social alienation would be expected to have an emotional reaction to those experiences, and respecting these experiences is seen by these liaisons as very important. This divide plays a role in disagreements about how to invite more participation. Those liaisons most interested in efficient processes within area commission meetings also tend to favor an area commission structure that follows a set agenda while controlling the number of participants in order to allow participants more time to engage in a more meaningful way. These practices follow White business/cultural norms referenced earlier in the report—specifically those related to a prioritization of efficiency over diversity of voice and the comfort of those already privileged by a process or arrangement.39 Other liaisons favor making more of the agenda available to the discussion of relevant ‘hot topics’ to make area commissions more relevant to a wider diversity of community members. As described within the Civic Engagement Environment framework, available research on inclusive civic engagement tends to favor practices that respect a wide variety of expressions, including emotional experiences and first-hand community knowledge, as well meeting agendas and placements that are relevant and accessible for a greater range of community members.4041 However, neither the Department of Neighborhoods nor the best practices document provide further guidance that would meaningfully speak to any of these ideas at this time.

6.0 Initial Steps for Change

The Columbus area commission public engagement apparatus faces challenges in providing an inclusive and equitable environment for meaningful resident engagement from both external and internal sources. While external patterns of racial inequity, development pressures, and civic engagement trends may continue to be present barriers, our research shows that the Department of Neighborhoods can nevertheless pursue powerful interventions to the apparatus to promote equitable and inclusive engagement.

6.1 Establish a Clarity of Purpose, and then Provide the Mandate and Supports to Support that Purpose (Three Interrelated Recommendations)

Our observations and interviews both highlighted that Columbus area commission meetings are often the ‘go-to’ setting for area residents to engage on a number of topics beyond zoning issues. Community challenges, such as housing, safety, and child welfare, are also discussed and decided in subcommittees. However, these issues can spill over into time reserved for the area commissions’ primary mission of advising on zoning variances for approval by the city. This works to create an engagement environment that is often inadequate for providing meaningful discussion and deliberation on a number of topics that are vital to those who are marginalized by structural inequities. As a result, area commissions in areas with heavy development pressure struggle to address these issues or adequately adjudicate zoning requests in an inclusive manner. Additionally, the variety of topics discussed at area commission meetings may ultimately map to city departments outside of the Department of Neighborhoods. In our findings, we found little in the way of formal processes to ensure participant requests and inquiries were connected to appropriate city personnel. Finally, the unclear focus of the area commission meetings often leads to the recruitment of potential commissioners who lack important knowledge or interest in zoning and planning matters. Given the foundational nature of zoning within the area commission meetings, these challenges often put area commissioners and participants in a set of circumstances in which it is unclear how community feedback should be prioritized.

In order to address these issues, we offer the Department of Neighborhoods the following recommendations:

- Establish internal discussions within the Department of Neighborhoods and with other relevant city departments in order to clarify and possibly limit the purpose and scope of area commissions to levels appropriate for city goals, resources, and departmental responsibilities;

- Provide additional trainings and resources to area commissioners who are members of the zoning subcommittee to ensure that they have the expertise required to fully participate and make decisions grounded in knowledge of zoning and planning processes; and

- Align formalized lines of authority between area commissions and the appropriate city departments based on the identified purpose and scope of area commissions.

6.2 Provide Mechanisms for Residents to Engage in Non-land Use but Neighborhood-relevant Issues

A constant theme among participants was the lack of time and/or structure within the area commission meetings for thoughtful dialogue on important neighborhood issues and relationship building. Some area commissions have been successful in adding platforms for issues unrelated to zoning and development that might allow for inclusive relationship building, but they tend to be those commissions with less development pressure. Additionally, area commissioners rarely have extra time to help facilitate these expanded offerings. This often leads to a general lack of trust between some community members and commissioners, as well as a lack of vital consideration of historical and contemporary effects of structural inequities and sometimes rapid community development. Moreover, it isn’t clear how those alternate activities relate to decision-makers at the city level.

Since area commissions can create subcommittees as they deem necessary, and since much of the important land use-related discussions and decisions of the area commission occur at zoning subcommittee meetings, we propose encouraging citizen engagement about land use and zoning matters at the subcommittee level. We encourage the city to help area commissions educate their communities about the best ways to engage their local commission about zoning and other community matters, emphasizing that most of the work takes place in subcommittees. We encourage area commissions to promote subcommittee meetings with the same tools currently used to promote regular commission meetings. Further, we encourage area commissions to consider creating subcommittees that facilitate regularized, community-level engagement opportunities specifically designed for deliberation about community resources and supports beyond zoning issues. These new opportunities could also provide a basis for creating equitable relationships between community members and city officials and, if promoted as such with residents, should alleviate some of the pressure that area commissioners feel in regular meetings.

6.3 Expand Tele-engagement and Other Remote Engagement Options

Community residents and even some commissioners expressed a positive reaction to the remote engagement options employed by area commissions during the height of the pandemic. While these measures were designed as a temporary means of continuing public engagement commitments while social distancing, they also opened the area commission meetings to a wider group of community members, many of whom were described as ‘the most difficult to reach’ and often face structural challenges to meaningful engagement. While the challenges related to transparency and legitimacy in remote engagement remain notable, examples from several cities compiled into the Urban Institute publication Community Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond provide many possible avenues of exploration for widening the space for engagement with new technology.

The research team is aware of the legal and statutory boundaries related to tele-engagement options, given state law regarding public meetings. In cases where entire area commission meetings cannot be made available for remote attendance, we recommend that the Department of Neighborhoods become more aggressive in seeking out ways to use social media, websites, and messaging apps like GroupMe to expand the ways in which they can keep community members engaged in various area commission activities. If alternative mechanisms for engagement are ultimately pursued, provisions to integrate tele-engagement should be included as much as possible in the initial architecture of the program(s). Finally, in those areas where there are legal challenges to the regular use of tele-engagement options for public participation, we suggest that the city and area commissions work to advocate for changes where appropriate.

6.4 Invite and Engage Participant Lived Experience into Area Commission Meetings

Our findings revealed that commissioners possess a wide range of competency and comfort when it comes to dialogue facilitation skills. Often, commissioners’ skills are based on experiences that they’ve gained elsewhere and, resulting in little uniformity in the skill set of area commissioners. Specifically, our research found that among commissioners, there was a decided lack of confidence in their ability to manage conflict, prompt healthy discussion, and create a sense of inclusion within the meeting. This uncertainty appears to be a primary driver in the adoption of strict and competitive engagement practices that ultimately close the space for healthy, deliberative, and meaningful dialogue in area commissions. Moreover, a significant number of liaisons also expressed discomfort with facilitating emotional or controversial topics. Inclusive engagement must provide a space for people to vocalize a range of expressions about their community, from the intellectual to the emotional. Additionally, residents often come to area commission meetings with a variety of community engagement traditions, styles, and skills that can best be harnessed within an environment of learning, relationship building, and caring.

We recommend that the Department of Neighborhoods provide more directed capacity-building for commissioners and participants in such areas as emotional intelligence, cultural humility, healthy conflict management, and rapport building. These skills can provide area commissioners with a strong foundation for creating a culture of inclusive engagement, cooperation, and mutual understanding. The Department of Neighborhoods currently provides a commendable amount of training related to conflict resolution and racial equity, and those efforts could be enhanced by the development (or co-development) of more in-depth workshops related to the topics mentioned above. Those training resources could also be developed alongside important partners, such as The Ohio State University, Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission, or The Urban League. The Living Cities publication Institutionalizing and Operationalizing Racial Equity in City Hall, Community and Beyond includes a section related to authentic community engagement that contains a wealth of skills that could be helpful for training purposes.

6.5 Create Processes to Actively Recruit Commissioners Outside of Current Networks with the Objective of Creating Inclusive Environments for Engagement

Because of the multifaceted nature of area commissions and their prominence as a primary source of community engagement, many different people with different sets of expertise and motivations are drawn to serve as commissioners. As was discussed earlier, those various motivations are often connected to different ideas about structural racism, the importance of inclusion, and the types of relationships that dominate area commission meetings. While these issues rarely intersect with existing bylaws regarding area commission procedure, they nonetheless have an important effect on inclusivity and equity within the area commission meetings themselves. For instance, without adequate attention, the relationships that area commissioners have with different sets of participants can make it less likely that those with different motivations or views will be heard with the same care and attention, no matter the explicit intentions of commissioners.

The Department of Neighborhoods can help counteract these challenges by providing resources and support to area commissions and liaisons to intentionally widen the networks for identifying new commissioners. Ensuring that all members of the community—particularly those representing traditionally marginalized communities—are actively invited to participate as commissioners can help ensure that a greater variety of voices are understood and heard in the community.

6.6 Provide Financial Compensation to Area Commissioners to Empower More Diverse and Equitable Leadership

The lack of financial compensation for area commission members is helpful in ensuring that those who volunteer to serve are motivated by a spirit of volunteerism. However, the current model does not support area commissioners in their efforts to create time for expanded area commission duties and/or capacity-building opportunities. Many commissioners expressed a lack of time to learn new skills or even become more familiar with existing best practices due to a lack of time for volunteerism. Many commissioners have full-time jobs, families, and other obligations that compete for time with their civic responsibilities. Offering a stipend to area commissioners may work to offset their financial needs, allowing them to possibly amend their work responsibilities so they can build greater capacity to facilitate equitable, inclusive, and meaningful deliberations within their respective communities.

6.7 Area Commissions Should Consider a City-wide Election Day to Promote Equity Between Commissions and Greater Participation Among Citizens